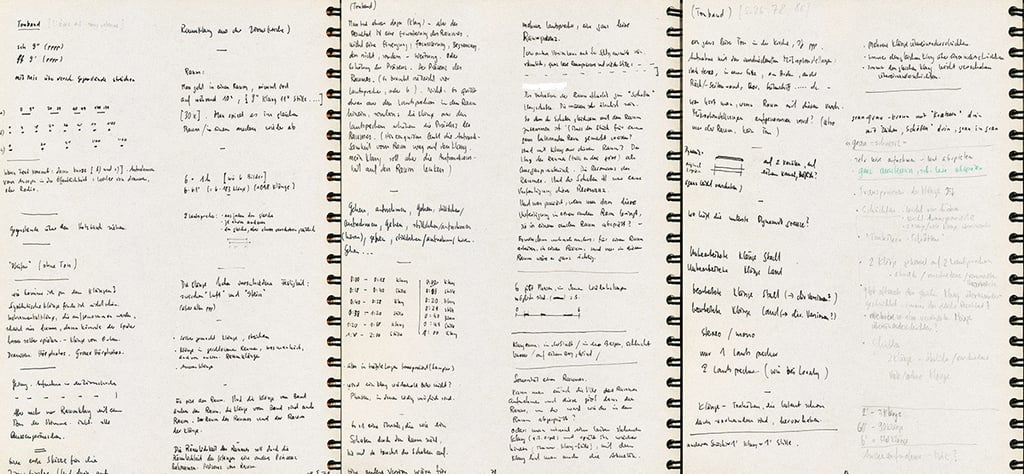

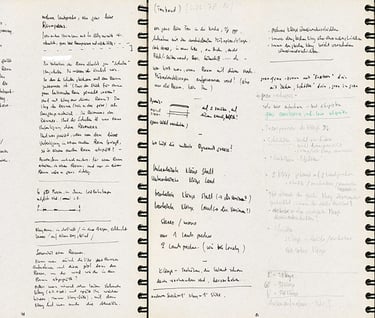

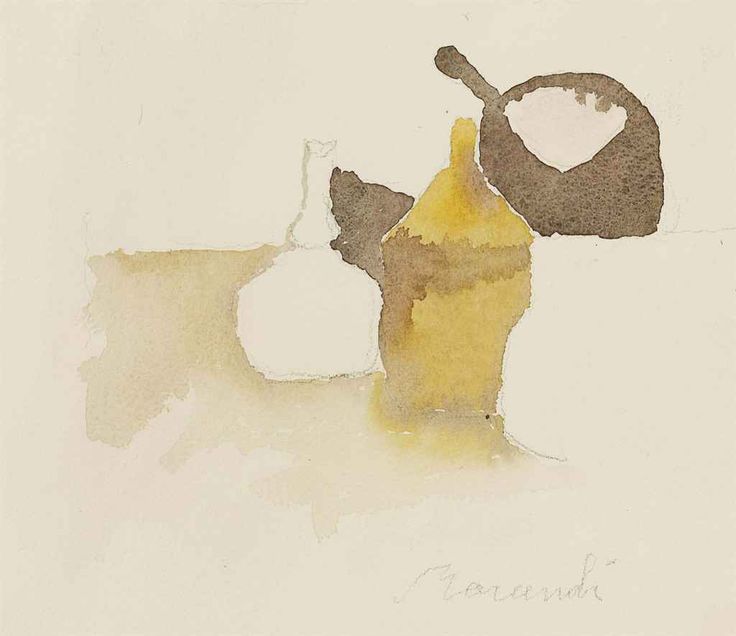

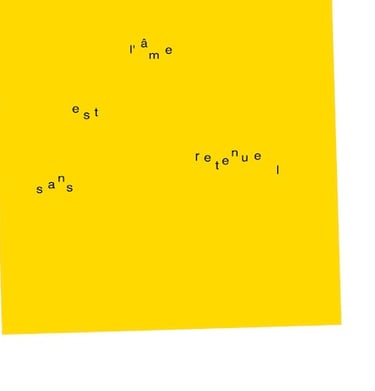

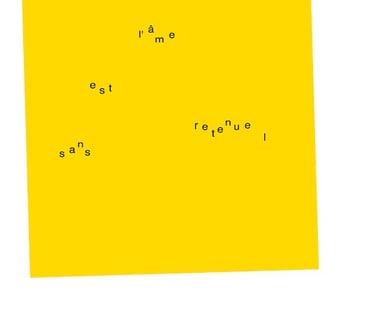

(above: sketch for l'âme est sans retenue II-3)

Listening to the entire series of all three pieces together (nearly 8 hours in total) also evoked in me a slow transition between seasons—watching the sunlight gradually weakens and the shadows increase as the autumn deepens—conjuring a tranquil flow of time. The tones (colors) of each silence seemed to change from white to light gray between l’âme est sans retenue I and II, and light gray to dark gray between l’âme est sans retenue II and III, with the entire atmosphere delicately increasing in calmness and darkness.

l’âme est sans retenue I

“In the pockets of reality that absence forms, as in the fissures between letters and the white spaces between written words, there are found the irretrievable, silent realities with which we are in dialogue.”

“Yet so vital is this mute and absent dialogue that it does not cease to reverberate in the memory and consciousness of the solitary self.”[1]

In l’âme est sans retenue I, linear stretches of field recording sounds quietly fade in, later fading out just as gradually, as if the music was taking a slow, long, deep breath.

On disc 1, muffled continuous stretches of sounds of field recordings, evoking something remote and immense (a distant waterfall, a hidden rumbling of the earth), fade in with a calm but intense and awe-inspiring presence. This atmosphere is not ominous or forced at all—nothing insisting or urgent—but instead peaceful with a white noise-like light texture. Though very vaguely, faint pitches, rhythms and dynamics can be perceived in the casual environmental sounds of field recordings. Each stretch of sounds has slightly different impressions of texture and a sense of distance—sometimes thin or thick, sometimes close or far. These changes of perspectives and textures create an open, three-dimensional feel of space.

In this seemingly stoic, monotonic structure of rumbling sounds, pale colors of fragments of reality make short, subtle appearances—the sounds of whistles, bird chirps, airplanes flying over, the whistle of a train—all vaguely coming from far away. These multiple layers of field recordings—both with muffled low rumbling sounds and with a slightly more realistic, light presence of environmental sounds—move in parallel with no discordance, simultaneously creating a clean contemporary edge and a visionary, idyllic atmosphere.

Each stretch of the field recording sounds fades out rather abruptly, and a long period of silence then prevails. In each border between sounds and silence, there is a hint of powerful (almost physical) force that glues the listener’s ears to the silence, as if each beginning of silence has an inconspicuous suction power. While the impressions of sounds and silence in the later l’âme est sans retenue III are rather dim, close to each other in texture (equally translucent, seemingly sharing the same gray area), l’âme est sans retenue I has more of a magnetic, brisk intensity in contrast.

Toward the end of disc 1, some small fragments of echoed distant music (similar to organ sounds) make vague appearances, followed by bird chirps or whistles, like a bit of nostalgic scenery briefly popped in from a distant memory.

Soon after the beginning of disc 2, a very long stretch of silence prevails. Then, the waterfall-like roaring sounds fade in with the chirps of a bird, soon both fade out. Sounds and silence alternate rather regularly in short spans, while maintaining the same whiteness of silence as in disc 1. A faint carousel-like music makes a brief appearance, followed by a short note of a wind instrument—all in a hazy, remote landscape.

Each stretch of silence seems to spread out its distinct, substantial presence clearly in the vast space, where the sounds of field recordings are carefully dotted in blurred autumn colors. Our ears are glued to the clean whiteness of silence, while a hint of poetic warmth seeps into our mind via sounds of the field recordings. By the time we get to the middle section of disc 3, the sounds of field recordings start to take on a calmer, more mystical atmosphere. In the middle section of disc 4, distant sounds of a church bell are heard solemnly and vaguely, followed by a stretch of silence. There is a sense that the atmosphere of the piece has somewhat changed after hearing this bell, as if the air was thickened and darkened.

On disc 5, a mysterious voice of an owl or another night bird is vaguely heard from far away, which becomes a trigger to deepen the night air further. This voice makes its appearance in all three pieces of the l’âme est sans retenue series, gradually more distinctively and longer as the series progresses. After a very long silence in the middle section, evoking the transition from night to day, a stretch of the waterfall-like roaring cuts in rather abruptly with a faint echo of harmonic tones behind. These roaring sounds fade off quickly, leaving a space of silence that feels wide awake. The atmosphere of the entire piece, which had been gradually increasing in shadow over the course of the first five hours, now seems to turn back to bright light—or to the starting point—as if we had gone through a long cycle of a day and came back to where we began.

Borders Disappear

By Yuko Zama

Jürg Frey's l’âme est sans retenue composition series

“Where there is space not covered by black ink, there otherness may lie: ‘White is the word for the word that writes itself’”

—The Book of Dialogue (Le Livre du dialogue), Edmond Jabès, 1984

During a three month stay in Berlin from October to December 1997, the Swiss composer Jürg Frey made field recordings in a park. He recorded distant environmental sounds by setting a microphone in the middle of the park, to collect various sounds—traffic noises, town noises, rumbles—any kinds of distant sounds which reached the center of the park via space. His microphones also picked up some closer sounds occurring in the park. Later he composed three electronic tape pieces in a series, l’âme est sans retenue I—III, in 1998—2000, using these field recordings as the source material. All three compositions have a similar minimal structure in which continuous linear stretches of sounds (of field recordings) and stretches of silence—all with changing lengths—alternatingly fade in and out.

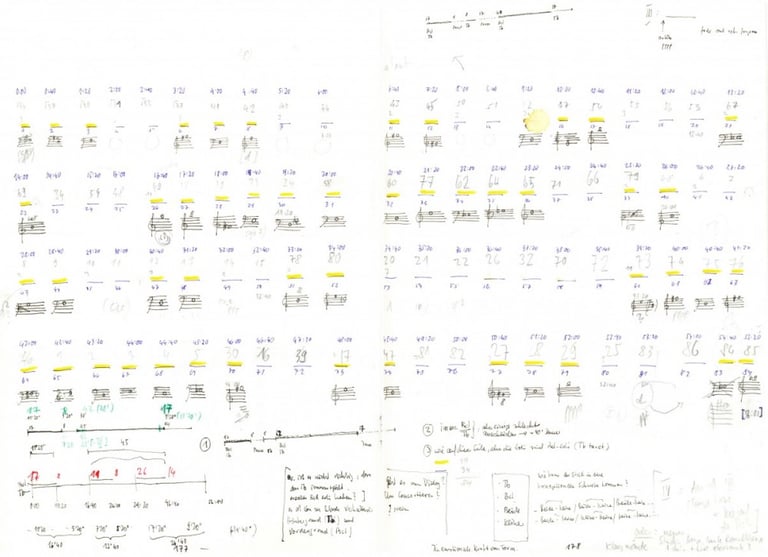

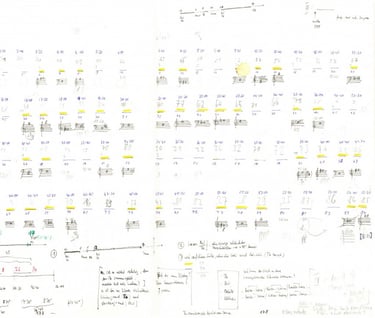

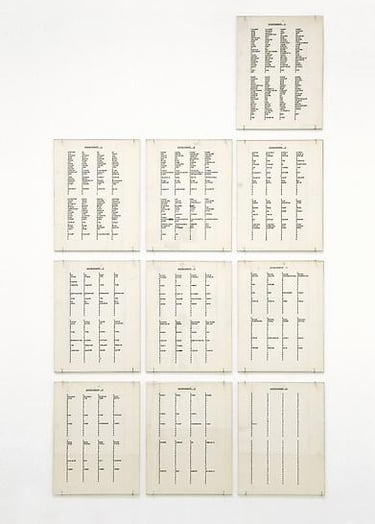

The first piece l’âme est sans retenue Iwas composed as a six hour piece, solely with the field recording materials Frey had recorded in Berlin. Frey previously made some sketches to overview the form of the entire piece and allotment of sound and silence in the six hour piece. Frey composed it following the details on these sketches and also his intuition, without scores. The only score he wrote and used in this series was a bass clarinet part in the second piece, which he played himself. The third piece l’âme est sans retenue IIIwas composed using overview sketches and field recording materials just like in the first piece. Frey intended to make this third piece as to be a closing piece (coda) in the series.

These three pieces resemble each other in structure, but one noticeable difference can be found in the length of the fade-in and fade-out periods of each stretch of sounds—shortest in the first piece, and longest in the last piece. This different length of transition periods also seems to affect our impression of the whiteness and thickness of the subsequent silence—and a sense of distance in each piece, opening a different door to a different space of silence.

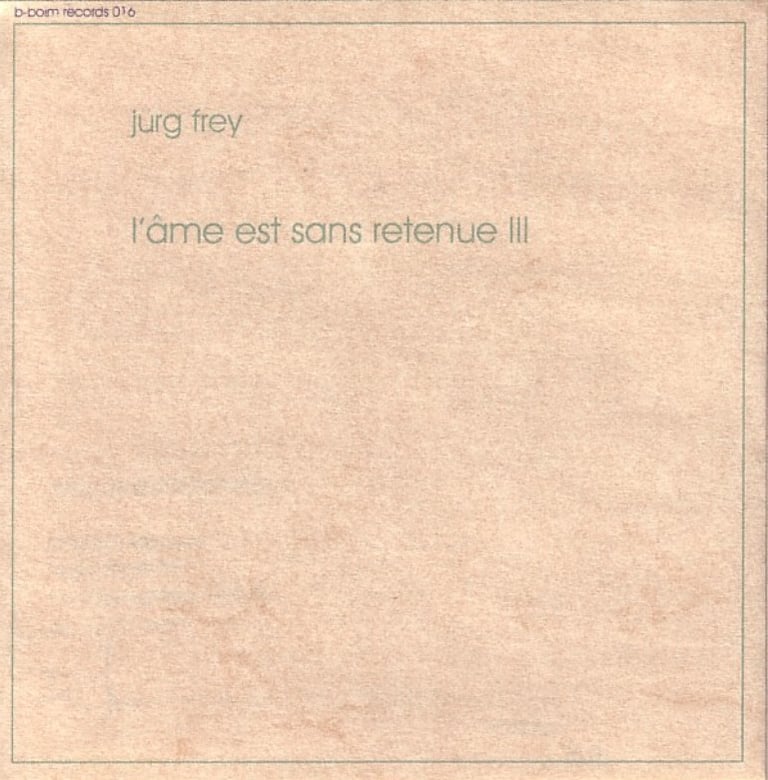

Among these three, the first released was l’âme est sans retenue III, a 66 minute composition for electronic tape, composed and mixed in 2000 and released in 2008 from Radu Malfatti’s b-boim label. The second release was the first piece in the series, l’âme est sans retenue I, released as a 5 CD set on the ErstClass imprint in October 2017. It was composed and mixed by Frey in 1998 as a six hour long piece, the longest piece that Frey has ever composed in his over forty years of composing. Frey told me recently by e-mail: “This piece is so fundamental for the understanding of my work, and it makes an important relation to the other works.”

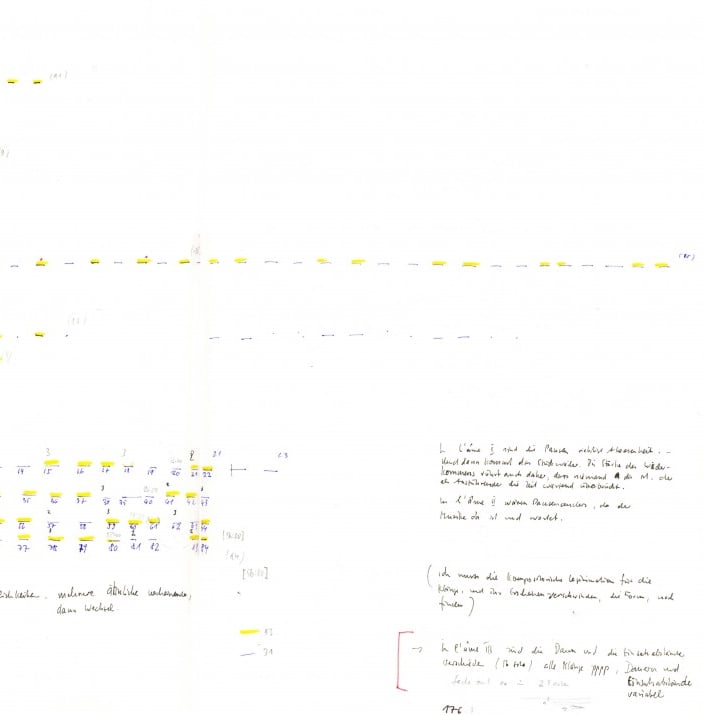

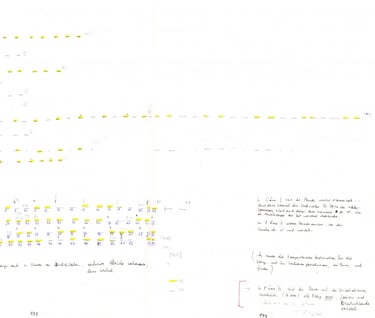

(above: sketch for l'âme est sans retenue II-3)

The second piece l’âme est sans retenue II was originally composed as a 56 minute composition for bass clarinet and electronic tape. For this piece, Frey made more thorough sketches of the details of the structure of field recording sounds and silence as a composition, and added the scores for a bass clarinet part. It was originally performed as a 56 minute piece, but after the second performance in Kittsee in 2000, Frey made a revised version as a 40 minute piece. It was later recorded by Fabio Oehrli at Tonlabor Bern in 2012, withFrey himself playing the bass clarinet part.

This second piece has not been released publicly yet, but I was lucky to have a chance to listen through the courtesy of the composer. In this piece, the fading in/out left a more neutral feeling than those of the other two pieces—somewhere between white and gray, or clear consciousness and calmness. Frey’s bass clarinet in this piece—occasionally appearing like a distant sound of a whistle of a train – is so subtle and natural that it seems to dissolve into the landscapes of the field recordings. His bass clarinet adds a personal color to this piece, as discreet as an autumn breeze, helping to connect the previous and the later pieces together into a single continuous series of three compositions.

(above: early sketch for l’âme est sans retenue I)

The clarity and the whiteness of silence are consistently striking, heightening our sensitivity and emerging as the essential quality of this piece. As the music gradually evolves, the power relation between sounds and silence seems to invert. Sound sections become opaque and meditative as the silence seeps into our brains, slowly expanding their white presence in our mind. This sense of inversion between sound and silence is surreal – as if our inner worlds were gradually emerging onto the surface of reality.

Frey seems to have composed this piece utilizing the physical power of silence and various sonic elements naturally emanating from the environmental sounds—pitches, rhythms, textures, colors, dynamics, overtone, and also our echoic memories of the sounds we previously heard—all placed into a vast expanse of time and space to form one music. The hidden power of silence is also portrayed more vividly and lucidly here than in any of his other compositions, as well as on the largest scale. Over the course of the six hours, the gravitational force of each stretch of silence moves its center and changes its tension slightly, carving an invisible sculpture of music composed of Frey’s contemplation—and each listener’s.

Even after listening to all 5 CDs of this six hour composition in a row, my ears did not feel tired at all—rather I felt my mind was purified or refreshed. The whole listening experience was intense but simultaneously soothing and introspective. In this piece, silence seems to belong to anyone’s inner world—not just to the composer’s. During the six hours of listening, the boundary between me and the music seemed to disappear without knowing, as if the music became a part of me. By the end of the piece, the border between my room and autumnal Berlin (or anywhere else), the border between the year 1997 and the present (or any time in the past and the future), the border between reality and unreality (or the outer world and the inner world), all seemed to dissolve into one vast, ambiguous, meditative sphere of silence with a sense of infinity. This sensation of unity was overwhelmingly beautiful.

Architecture of Silence

Frey wrote an essay titled Architektur der Stille (Architecture of Silence) in 1998[2], around the same time he was composing l’âme est sans retenue I. This essay showed us that Frey was particularly focusing at this time on how physical relationships between sound and silence can affect our perception of space and time, and outlined the unique philosophical approach he used to compose the series of l’âme est sans retenue.

“In silence, a space opens, which can only open when the presence of the sounds disappears. The silence which is then experienced derives its power from the absence of the sounds we have just heard. Thus periods of silence come into being, and then comes the physicality of silence.”

“There are pieces in which the absence of sound has become a fundamental feature. The silence is not uninfluenced by the sounds which were previously heard. These sounds make the silence possible by their ceasing and give it a glimmer of content. The space of silence stretches itself, and the sounds weaken in our memory. Thus this slow breathing is created between the time of the sounds and the space of silence.

—Jürg Frey ‘Architecture of Silence’ (1998)

This concept in Frey’s text was exactly the same sensation that I had when I was listening to the Quatuor Bozzini with Isaiah Ceccarelli and Noam Bierstone on percussion performing Frey’s Unhörbare Zeit live in NYC in August 2017. During this concert, the sounds and silence seemed to gradually interchange their nature over the course of the 36 minute performance—as if light and shadow inverted—and silence came to life. In the slowly evolving music, silence became more powerful and intense, and sounds became calmer and more meditative – and both deepened and widened the space-time of the room we were all in.

This clarity and whiteness in the silence after the sounds disappeared in Unhörbare Zeit came back to me when listening for the first time to the recording of l’âme est sans retenue I. There is a sense of absolute disconnection between the two realms of sound and silence in this piece. What makes it so unique and fascinating is the way Frey infuses two different natures into a piece at the same time. Affinity and disconnection, whiteness and grayness, closeness and distance, openness and obscurity, coolness and warmth, minimalism and impressionism—these seemingly contradictory natures co-exist in the same moment throughout the piece, alerting and sharpening our consciousness while embracing our soul. This music seems to soothe and stimulate our brains at the same time. With this uniquely, fascinating double nature underlying the atmosphere of the piece, this music never falls into either monotony or artificiality over the course of its six hours.

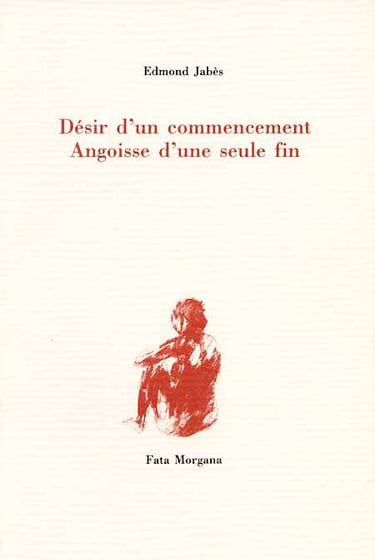

Poetry and Art in Frey’s Music

The title of Frey’s composition series “L’âme est sans retenue” is a quotation of a single, isolated sentence from French poet and writer Edmond Jabès’s book Désir d’un commencement, Angoisse d’une seule fin (Desire for a Beginning, Dread of One Single End), his final book. [3] In Jabès’s book, a large portion of white space is distinctly present between sparsely arranged blocks of sentences. In this book, some particular words appear more than once in the blocks of sentences – light, day, night, water, memory, shadows, river, dreams, thought, white, soul, bird, death, silent, nothing, abyss, void – some of which are resonant with the vague images evoked in Frey’s l’âme est sans retenue series. The title of the book “Desire for a Beginning, Dread of One Single End” also seems to be faintly reflected in the way each stretch of sounds appears and disappears abruptly in this piece.

In a different book Le Livre des marges (The Book of Margins), Jabès also wrote about his keen perception of “other” (or unwritten words) that inhabit the spaces between and around the written words. This Jabès conception of dialogue in a relationship with silence and absence seems to be closely linked to Frey’s underlying concept of the l’âme est sans retenue series, in terms of a relationship between sound and silence giving a substantiality to silence with a sense of disconnection (or absence) and distance.

“Every blank page contains hidden in its “depth” an infinity of words that become truly “other,” especially as the page becomes filled with writing. The written words push the unwritten words to the margins where they lie dormant. This silent, invisible, “other” writing also inhabits the spaces between the lines or peers out from between letters. Where there is space not covered by black ink, there otherness may lie: ‘White is the word for the word that writes itself.’” [4] —From Edmond Jabès Le Livre des marges, II: Dans la double dependance du dit (1984)

Also, Richard Stamelman, the author of The Dialogue of Absence (an in-depth study on Edmond Jabès’s books), pointed out that Jabès’s books were deeply associated with the notions of distance, absence, and exile—or a nomad wandering in alien lands.

“Alterity dominates Jabès’s books primarily because his writing is nomadic. It is the exilic speech of a wandering, deracinated people. Since exile is founded on the absence, distance, and unpossessibility of a lost homeland, as well as on the alterity and difference of the exiled nomad wandering in alien lands, the writing of exile is also charged with otherness. (…) Thus, Jabès often speaks of the book-in-the book, that hidden, invisible writing which every book contains and which every word tries to “develop” (in the photographic sense of the term). (…) Book, page, line, word, letter are all inhabited by an unseen otherness, an effaced writing, a “contre-écriture”, trailing after the dark writing on the page like a white shadow.” [5] —From Richard Stamelman—The Dialogue of Absence (1987)

Frey’s silences in the l’âme est sans retenue series seem to be parallel to this “invisible other” (Jabès) or “invisible writing” (Stamelman) of Jabès’s books. Silence emerges between stretches of sounds in Frey’s composition series, with its quiet breath gradually filling the space of listeners’ inner worlds with clear whiteness. This silence gradually increases its substantiality, through a cloudy transition of something invisible becoming reality—like a photographic image emerging on a printing paper. Throughout the entire piece, we hear/recall/predict the presence of silence lingering around the sounds “like a white shadow” just like the white space (unseen otherness) trails after the dark writing in Jabès’s book. Frey seems to cast a faint shadow of Jabès’s notions of distance, absence, exile over the entire atmosphere of the l’âme est sans retenue series, when he recorded distant environment sounds for three months in a Berlin park—a sort of an “alien land” to him, far away from home.

In the l’âme est sans retenue series, a stretch of silence lasts sometimes as long as ten minutes or so between sound sections. We may wonder if there will be another sound or not after such a long silence. This is the clearest time when we get closest to the core of this piece – to face silence. Silence may connect or disconnect two units of sounds – we will never know until we hear what is coming. Silence leaves us hanging in the air. To face the silence is like looking into a mirror that reflects our inner self – as Jabès writes, “The hidden dialogue, in its augmented and anxious inaudibility, perseveres in the inaccessible depths of ourselves.” [6]

In anticipation for the next sound, our perception is sharpened and we can sense anything which may arise in the absence of sound. And in this extreme depth of the silence, we may feel as if we were looking into a valley of uncertainty from a cliff with a sense of awe, fear, expectation, hope, anxiety, longing, despair, or even our hidden creative energies or our other self which may not be discovered otherwise. If we have good ears, we can hear the truth or the answer to our question in the silence. In this infinite depth of silence, our souls can experience so much with no limit.

What gives life to Jabès’s dialogue is this invisible presence of silence. Jabès also writes in The Book of Dialogue: “Lack is the vertigo of the book. The edge of words cannot hope to win out over the abyss.” “This lack was my place.” This text of Jabès’s evokes in me the strong vertigo effect that I have had from Morton Feldman’s music when I was repeatedly listening (and was addicted) to his music at some point in my life. This vertigo effect was the reason why I was deeply fascinated with Feldman’s music, but at the same time, it was the reason why I had to stop listening to it because of its overwhelming effects on me—a vertigo.

Frey was strongly influenced with Feldman’s music in the 1980′s as a composer as heard in his Streichquartett (1988), and also as a clarinet player, conductor and researcher. After this intense period of being deeply immersed in Feldman’s music, Frey started to find a way to seek out his own music, leaving behind the Feldman influence. Frey told me about this period in our recent e-mail conversation: “It was not easy then to come out of Feldman’s world, and my music in the 1990 also may be heard as a struggle to leave Feldman and to find out, what is Feldman and what is me, where is my place beside Feldman. One possibility for me was my work with lists (and l’âme est sans retenue is also a list of sounds). With my lists, I had not to deal with all the questions Feldman taught me. It was a clear, simple and not Feldmanesque procedure, a flat thing, and at the same time, I could work with the silences, I could explore the silences as material, as an constitutive part of my compositions.”

Frey applied a list of sounds which are resonant with the several keywords from Jabès book Désir d’un commencement, Angoisse d’une seule fin, while using silences also as materials to compose this l’âme est sans retenue series. His clear-cut straightforward approach in this series is exactly what makes this composition series distinctly different from Feldman’s music. While creating the slightly enigmatic atmosphere similar to Jabès’s book, Frey established his own solid approach to composing music with a calm, modest but distinguished tones via a sense of distance in this l’âme est sans retenue series – which can be marked as a milestone in his career of composing.

The idea of substantiality of space and silence, which stands out both in the absence of written words (in Jabès’s books) or sounds (of Frey’s music), can be also linked to Carl Andre’s poems. This American minimalist artist, who is well known for his sculptures and poetry from the sixties, is one of Frey’s favorite artists. When I saw a picture of Andre’s typewriter poems AUTOBIOGRAPHY 1[-10], I immediately saw a close connection to Frey’s l’âme est sans retenue in the modular-like formation of words and sentences in relation with space. Yasmil Raymond, the curator of Dia Art Foundation, portrayed the essence of Andre’s poems with the quotes below, which also evoke in me the sound structure of Frey’s l’âme est sans retenue.

“Andre’s poems (also referred to as ‘typewriter drawings” and “planes”) have shown his effort to dismantle any traditional notion of lyricism, extending their breaking force to grammar itself. Confronted with a page where words often compose figures rather than sentences, the reader’s eye looks instead for connections between lines, columns, and blocks.” [7]

“He’s experimenting here with space on the page, relating to language in the manner of concrete poetry in a way. (…) Rather than primarily visual, the writings are definitely language based, but he treats language as matter in space, side by side, unit by unit.” [8]

This concept of Andre’s poems as described by Raymond seems to be linked to the sound structure of Frey’s l’âme est sans retenue as well, in the sense that Frey disassembled the field recordings, breaking down the conventional notion of sound in nature, to create a white noise-like minimal texture (the muffled rumbling sounds) as the core element of each sound section. These white noise-like sounds seem to be detached from lyricism or realistic narrative connotation, simply used as a component of the core sound where its texture matters. Also, the visual impression of the installation version of Andre’s AUTOBIOGRAPHY 1[-10] with all 10 pages together evokes a similar gradual transition between sound and silence as the l’âme est sans retenue series, where each stretch of sounds recedes into silence while the substantiality of space expands.

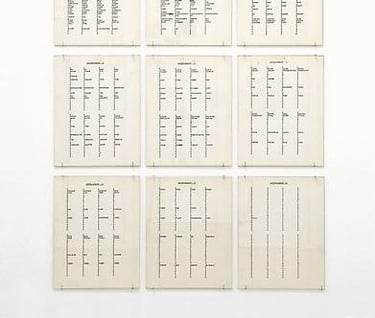

While the basic structure of the l’âme est sans retenue series contains a keen sense of simplicity and intensity similar to minimal art, it never feels cold or impassive. There is also a warm breeze of Impressionism or Romanticism occasionally blowing through the clean minimal structure, often a signature of Frey’s compositions. Even though there were almost no obvious tonal music or melodies here, in several spots during the six hours, I felt as if I were hearing a hint of distant music—like a faint echo of some distant orchestral music lingering in the wind—which must have been actually emanating from the mixture of fragments of field recordings. Each time this occurred was such a breathtaking moment—a translucent mirage of warm scenery suddenly formed in our auditory sensation – just like the images of still lives in the Italian painter Giorgio Morandi’s watercolor paintings sometimes start to seem like nostalgic landscapes of autumn villages.

Frey talked about this link between his music and the works of Morandi, one of his longtime favorite artists, in his 2015 interview with Brian Olewnick on the label Another Timbre’s website. [9]

In this interview, Frey said that Morandi’s works overlap with the realm of abstract painting, even though they are always figurative. What Frey likes in Morandi’s work is how a figurative painting can contain the quality of abstract paintings, so a figure of a cup or a bottle may also evoke something abstract. He mentioned this in reference to his 2015 release ‘Grizzana and other pieces 2009-2014′ (at 86-2) at the time, but these connections between Frey’s music and Morandi’s artworks can be observed in his earlier compositions as well. Frey told me that he came to know the works of Morandi around 2004-2005, so he was not yet familiar with Morandi’s works when he started composing the l’âme est sans retenueseries in 1997, but the close similarities in the essence of the work seemed already there in Frey’s early compositions.

“With this image (of Morandi’s paintings) in the background, you can listen to many of my pieces from the past. Sometimes it goes more to the abstract side, sometimes more to the figurative, but in general it takes a clear position between the two. It happened unconsciously in the earlier pieces, and later I discovered this image of abstract / figurative to find words to speak about the music. (…) Let me finish these reflections on Morandi with a quote. Sean Scully wrote in his essay about Giorgio Morandi: “His brush stroke is in complete philosophical agreement with the subject, the scale and the color of his painting. It is expressive, though it is modest, and not so expressionistic as to disturb the sense of meditative silence that inhabits all his works.”

—Jürg Frey, from his interview in 2015

This description of Frey’s music by himself, “sometimes it goes more to the abstract side, sometimes more to the figurative, but in general it takes a clear position between the two (abstract/figurative)”, is exactly what we find as the essential, unique nature in his music. Also, the description of Morandi’s brush stroke[10]—which is “in complete philosophical agreement with the subject, the scale and the color of his painting” and “is expressive, though it is modest, and not so expressionistic as to disturb the sense of meditative silence that inhabits all his works”—captures the truth of Morandi’s artworks, and at the same time, captures the truth of Frey’s compositions as well.

When I look at Morandi’s watercolor works, the still life objects and the room air surrounding them that he paints feel equal in substantiality—neither the objects nor the air dominate the space. The air in the painting feels as thick and substantial as the objects, and the objects feel as light and transparent as the air. And sometimes the texture of the objects and the air start to feel inverted in the scene. The air in the picture feels as if it were breathing with life, while the impressions of objects start to disappear into transparency—in the ambiguity where objects seem to move back and forth at the border between reality (figurative) and unreality (abstract). But this ambiguity does not bury either the objects or the air in blankness. Through the hazy tones of Morandi’s watercolors, the essence of the piece or the soul of the artist seems to emerge through a thin veil of mist. And this is a very similar impression that I get from Frey’s music.

What seems to be so fascinating about Morandi’s artworks, also overlapping with the uniqueness of Frey’s music, is this mixed sensation of ambiguity and clarity – or clarity filtered through ambiguity. The sense of distance between Morandi’s artwork and the viewer may feel both close and far at the same time—like looking at a far distant landscape on a hazy morning, or like looking at objects plainly floating right in front of our eyes. Space and time that were originally captured by the painter seem to be flowing out of the frame, connecting both to a much wider space and also to the present time as if we were breathing the same air. The objects in a peaceful household scene in Morandi’s paintings can evoke anything in our mind—just like Frey’s music composed with minimal sounds and silence can evoke in us something larger and eternal—beyond the boundary of space and time. This unique illusion can be sensed extremely delicately in an exquisite balance both in Frey’s music and Morandi’s paintings.

Another aspect I feel Morandi’s artworks and Frey’s music have in common is the horizontal expansion in the calmness—a feel of calm air gently and naturally flowing in a tranquil landscape—which also evokes in me both a sense of distance and the anti-emotional modernism of Erik Satie’s music, bringing a perceptual illusion of motion to the stillness.

This unpretentious nature of the silence, that seems to ‘move’ in a modest, quiet manner in Frey’s piece, is often another signature of his music. Frey described his works as ‘silent architecture’ again in his text

Weite der Landschaft—Tiefe der Zeit (Width of Landscape—Depth of Time) in 2008. [11]

“My music is silent architecture. It is like the silence of a room, a wall, a landscape like places or squares that are silent. It is silent music, but it is not absent. It is not speechless, and it does not negotiate virtuosically on the verge of silence. In its quiet presence, everything is there: colors, sensations, shadows, durations.”

“… the light fresh air—autumnal and yet reminiscent of the summer—which lends personality to the air. This breath, which lends personality to the air, is my idea of my music.” — Jürg Frey, Weite der Landschaft – Tiefe der Zeit (2008)

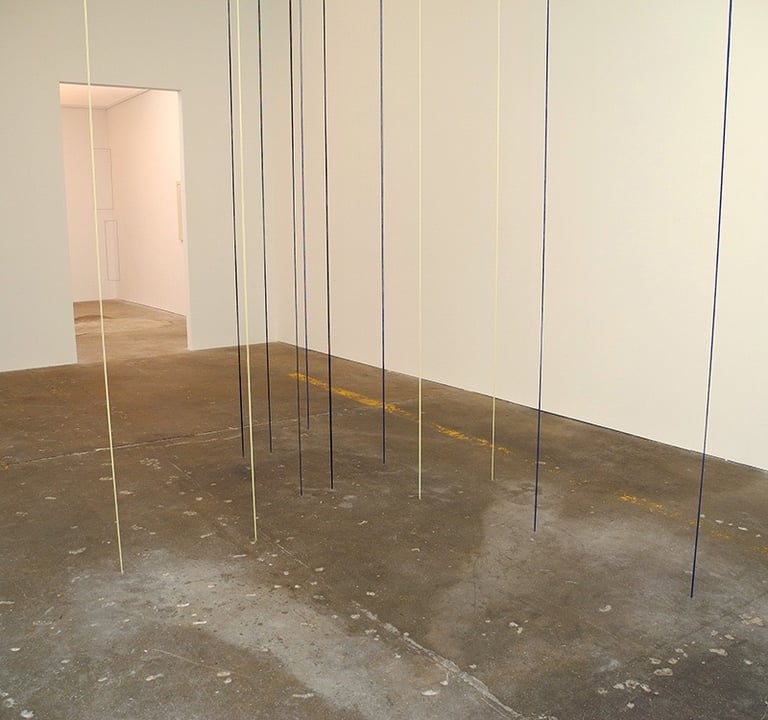

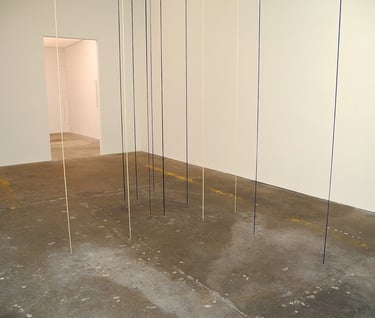

The very last sound of each of the three l’âme est sans retenue compositions vanishes into space—sort of bluntly—with no dramatic sensation left behind. This reminds me of Fred Sandback’s space sculptures, in which the end of a string of thin translucent acrylic yarn seems to silently disappear into a wall or a floor as if it had been all illusion. (Recently in my conversation with Frey, he mentioned that he feels a strong connection to Fred Sandback’s work in regards to the notion of space.)

Just like Sandback outlined the shape of his sculptures using thin strings and wires in an empty space, with the l’âme est sans retenue series, Frey created an invisible but substantial four-dimensional artwork using sounds and silence in a frame of time and space. His clear-cut perspective underlies the atmosphere of idyllic ambiguity here. While maintaining slight, occasional connections to reality, this series of compositions also brings poetic, illusionary sensations as if we were hearing music in the fragments of field recording sounds. Frey infused these senses of reality and unreality throughout the entire series of l’âme est sans retenue with his great intuition and careful layout of sound and silence, all perfectly balanced.

Beyond Space, Beyond Time

It was surprising to learn that Frey composed this piece in the late 90′s, when it was rare for composers to incorporate field recordings into such a large-scale piece with such a subtle touch. The visionary images of a slow transition between seasons—or a hint of Romanticism—are only vaguely sensed in these pieces but incredibly beautifully portrayed, which is a similar impression I often get from the most delicate, masterful performances of Romantic music. Also, the contemporary edge of this series still feels keen and fresh today in spite of the fact that they were composed almost twenty years ago.

By keeping its structure strictly simple with no excess elements while creating the entire atmosphere with a mist of ambiguity, this seemingly low-key series of compositions have obtained an indefinite value that can surpass the restrictions of time and space. The horizontal calmness, where numerous minute changes occur almost imperceptibly—sometimes in sounds, sometimes in silence (metaphorically)—over the course of approximately eight hours, can be an answer to the future form of music that we may feel like listening to for a very long time with no psychological fatigue. Even after listening to this series constantly for weeks, still these mesmerizing silent architectures, carefully composed almost twenty years ago, are the very music that my ears currently want to hear—again and again.

Frey composed these three pieces using silence as the essential component of the composition by pulling out unique dynamics from the relationship between sounds and silence. Silence is not just a pause or a blank space in his compositions—it contains intense artistic beauty that directly touches our souls with its substantial power—just as truly great poetry and art do. But above all, while being deeply connected to the profound worlds of poetry and art, this l’âme est sans retenue series certainly has a genuine authenticity as a great composition—in accord with classical music aesthetics—no matter how far away it may feel from the tradition.

Frey told me about this series, “It’s about how ‘normal’, ‘regular’ things are transformed – by the work of composing, by decisions, by intuition, by the ear – to an art work.” Frey seems to intuitively know exactly how the composition should be assembled, precisely applying textures, colors and shadows of sound and silence on a white canvas of space and time. In this composition series, every element seems to be consonant with each other like tonal music. When he talked about his early piece Lachen und Lächeln (1978) – for soprano, violin, clarinet, horn and piano, based on a poem by the Swiss writer Robert Walser – in his above-referenced interview with Olewnick, he said, “I didn’t have a clear awareness when I started writing the piece, but had a strong feeling when I had finished it that yes, composition was something for me to go on with. Looking back on this piece today, I recognize characteristics, already present in the piece, which are important for my later work. It happened somehow in this early piece, and I remember the reason that I wrote this kind of piece was not as an exercise in compositional technique or for aesthetic considerations, but because I wanted to write something I liked to listen to.” I think this remark of Frey’s explains well why his music is always so captivating on a personal level.

The French title of this composition series ‘l’âme est sans retenue‘ means “The soul has no restraints”[12]. When you listen to it, you may feel as if your soul was traveling somewhere beyond the boundary of time and space, navigated via the gravity of silences throughout in these extended compositions—a series I believe will be remembered as a timeless masterpiece in contemporary classical music history.

—Yuko Zama, September 2017

Footnotes

Richard Stamelman The Dialogue of Absence – a study on Edmond Jabès (Wesleyan University, 1987) p. 13

First publication of this text in German: Jürg Frey Architektur der Stille, in Seiten für freies geistiges Schaffen 3/98, Baden 1998 First publication of this text in English: Program note for “Three Instruments, Series“, July 1999, Northwestern University, School of Music, Evanston 1999 (Translation by Michael Pisaro)

Edmond Jabès Désir d’un commencement—angoisse d’une seul fin (Fata Morgana, 1991). English publication is Desire for a Beginning, Dread of One Single End (Granary Books 2001) translated by Rosmarie Waldrop *Frey quoted the sentence from a German French publication from Stuttgart (1992)

Edmond Jabès Le livre des Marges II: Dans la double dépendance du dit (Montpelier: Fata Morgana, 1984) p. 25 . *English translation was quoted from Richard Stamelman The Dialogue of Absence—a study on Edmond Jabès (Wesleyan University, 1987) p. 7

Richard Stamelman The Dialogue of Absence—a study on Edmond Jabès (Wesleyan University, 1987) p. 6

Edmond Jabès Le Livre du dialogue (The Book of Dialogue) (Paris: Gallimard, 1984) p. 12 ↩*English translation was quoted from Richard Stamelman The Dialogue of Absence—da study on Edmond Jabès (1987) p. 11

Program note for Carl Andre, Sculpture as Place, 1958-2010 by Yasmil Raymond, the curator of Dia Art Foundation (Dia: Beacon, Reggio Galleries, May 5, 2014 – March 2, 2015)

Maximum Minimalist: The Carl Andre Retrospective / Interview with co-curator Yasmil Raymond by David Ebony (July 2014) ↩http://artbooks.yupnet.org/2014/07/29/minimalist-carl-andre-yasmil-raymond-david-ebony/

Jürg Frey interviewed by Brian Olewnick (2015), from Another Timble label website: ↩http://www.anothertimbre.com/freygrizzana.html

Giorgio Morandi: Resistence and Persistence by Sean Scully (Artcritical Online Magazine) 2008 ↩http://www.artcritical.com/2008/09/01/giorgio-morandi-resistence-and-persistence/

Publication: Jürg Frey Weite der Landschaft—Tiefe der Zeit, in Positionen 75, Berlin 2008

Edmond Jabès Desire for a Beginning/Dread of One Single End (Désir d’un commencement – angoisse d’une seul fin) (Granary Books 2001) *English translation by Rosmarie Waldrop, P. 38 ↩

About the Images

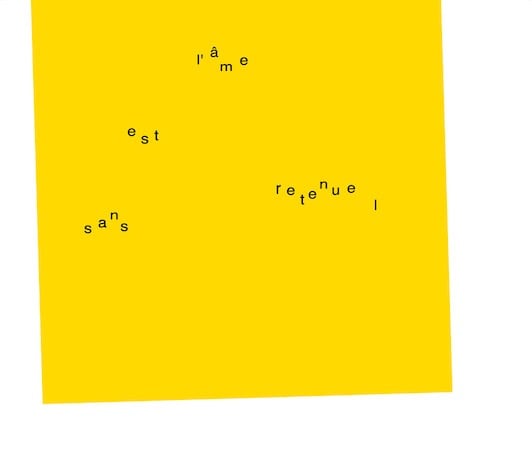

Cover art of Jürg Frey l’âme est sans retenue I (ErstClass 002-5), designed by Yuko Zama, inspired by Jürg Frey’s original artwork and his first composition Stück (1975) #36

Cover art of Jürg Frey l’âme est sans retenue III (b-boim 016) 2008

Sketch for l’âme est sans retenue II (3), drawn by Jürg Frey

Sketch for l’âme est sans retenue II (4), drawn by Jürg Frey

Early sketch for l’âme est sans retenue I, drawn by Jürg Frey

Quatour Bozzini with Isaiah Ceccarelli and Noam Bierstone on percussion performed Jürg Frey Unhörbare Zeit (2004-06) at The DiMenna Center for Classical Music, NYC, August 4, 2017. The concert was as part of the 2017 TIME SPANS Festival. (Photo by Yuko Zama)

Edmond Jabès Désir d’un commencement—angoisse d’une seul fin (Fata Morgana, 1991) *Frey quoted the sentence for the title from a German French publication from Stuttgart (1992)

Carl Andre—AUTOBIOGRAPHY 1[-10] ca. 1958-1959, typewriter carbon on paper, 10 15/16 x 8 7/16 inches, 10 pages, ARG# AC1959-001

Giorgio Morandi—Natura morta (Still Life), watercolor, 1960

Giorgio Morandi—Natura morta (Still Life), watercolor, 1959

Fred Sandback—Untitled (1985/2012) (Sculptural Study, Vertical Construction with white and yellow acrylic yarn) at Schiffbau in Zürich, 2012 (Photo by Jürg Frey)

Fred Sandback—Untitled (1987/2012) (Sculptural Study, Twelve-part Vertical Construction with black, blue, and light yellow acrylic yarn) from the exhibition Decades (Works 1968-2000) at David Zwirner, NYC, March 2012 (Photo by Yuko Zama)

About the Author

Yuko Zama is a music writer, photographer, translator, designer and co-producer for Erstwhile Records and Gravity Wave, and is the lead producer for Jürg Frey l’âme est sans retenue I (ErstClass 002-5)

In 2018 she started her own Label elsewhere.